ON OUDEZIJDS ACHTERBURGWAL, a street and canal at the center of De Wallen, Amsterdam’s Red Light District, a woman sits in a window on a Friday morning staring into an overcast late November day. She is dressed only in her bra and panties and her hair hangs loosely about her shoulders. She is a voluptuous, pale character with doll-like features and pink lips and her face reveals a mixture of morning grogginess and utter resignation. This is the face of a woman who has seen everything and done everything, and everyone, and she seems bored by the world.

Upon seeing her from across the canal, I give her a friendly wave and she waves back to me. For a moment, it feels like we are old school chums. There is a sense of camaraderie there. Though I am a writer and not a prostitute, I suppose we are in the same kind of business. We give pieces of ourselves away for financial rewards. My soul is written with words onto paper. Her soul is pressed into flesh. She is someone’s daughter, someone’s sister, maybe a mother.

But this has been her fate, to sit here tiredly selling herself, while my fate is to head off to Rotterdam, to give a talk about what it’s like to be a writer who writes in cafes. I feel disgusted, of course, for myself, for the woman, for the world. I feel disgusted as a man, too. But then I wonder why as people we are so often disgusted with ourselves and with our day-to-day lives. As the weekend crowds line the canals of the Red Light District and the sinister laughter of throngs of British men (and women) echoes up and down the alleys, one can only feel disgust.

This is the heart of the decadent West, a West that we have convinced ourselves is dying every day. The official capital of the European Union is in Brussels, but its spiritual heart might be right here by these old canals with their erotic boutiques, 5D pornographic theatres, and sex workers.

Our revulsion and gloom about our future is only compounded by the migrant crisis and climate change. I recently read an article in The Guardian where it said that only one in five female scientists planned to have children, to spare their would-be offspring this shame of being born. No one else should have to contend with the endless famines, wars, hurricanes and droughts.

They want to save the world and so they choke off its future, as if they were solely responsible for all its sins and misfortunes. As demographers forecast our societies will only shrink more, people turn to animals for companionship. There are social media sites for cat and dog owners where their pets can confirm they’re going to meetups at the park, or share photos in a group chat. I suppose the dogs can wish each other a happy birthday. Because animals are innocent and people are guilty. This is how we have learned to think about ourselves. This is the future we are building for ourselves, an indulgent childless future of pet social media.

But hasn’t it always been like this? This is what I think that morning as I wave to my newfound Dutch friend over the canal. She is certainly not the first woman to live this life or have this fate. There are many others. I pass by them as they prepare for the day. Then I turn the corner.

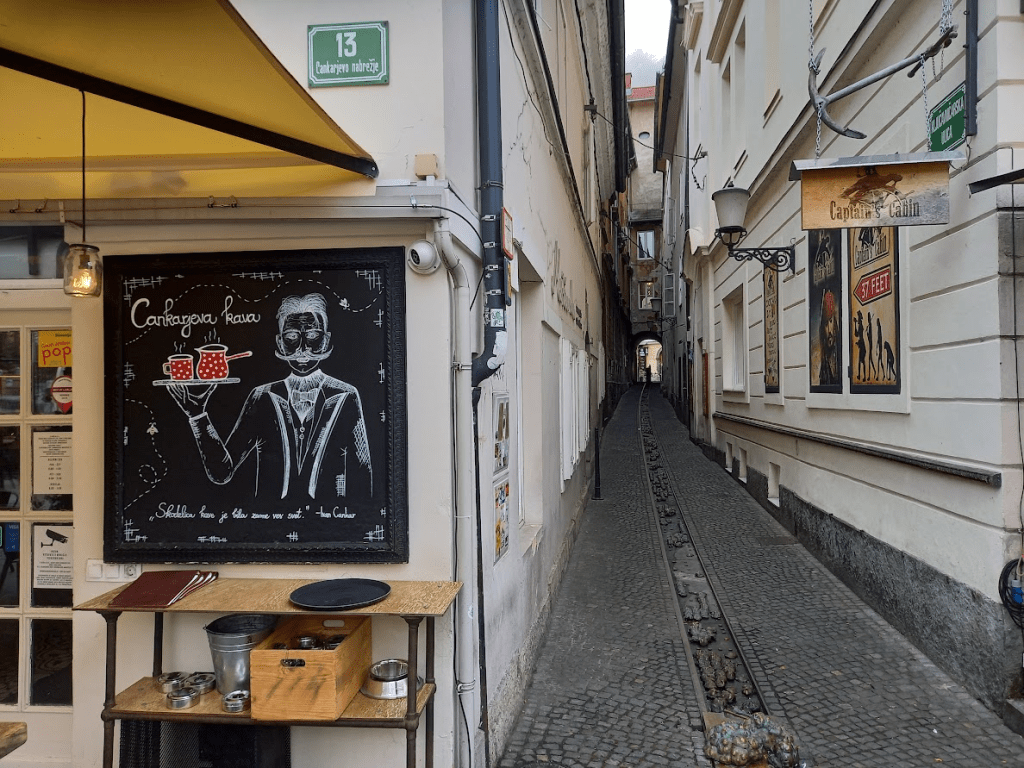

ON THE NEXT MORNING in the Red Light District, the municipal workers sweep up broken glass and soggy french fries and the ravenous seagulls attack piles of trash. This is how yesterday is replaced by today, but the bakeries and cheese vendors are already open, their shops glowing with warm, inviting lights. Life tumbles sleepily forward in Amsterdam, like an old man fumbling for his keys. At night, the city is a hubbub, a bazaar. Whatever you want to eat, you can find it. Whatever you want to see, you can see it. Whatever you want to do, you can probably do it. The Dutch are a tolerant people and that tolerance has become a foundational element of what we call European or Western values. We measure our Westernness according to the number of rainbow-colored Pride flags that hang outside of bars, or by the casual way we smoke cannabis.

We unbutton our top button and walk down Oudezijds Achterburgwal, waving at the women.

We are a free people, we tell ourselves, free people who can do whatever they want and listen to whatever they want. We can spend part of the night in a record shop, as I did, digging through the record bins, engulfed in green marijuana smoke, unearthing treasures by Jamaican and Zydeco bands.

The Western life can be a comfortable life, one where the main existential question is, “How should I spend my Friday night?” Or, “What concert should I go to?” One can just while away the days, in pursuit of personal satisfaction, pleasure, what some call happiness. In corners of the world like Amsterdam’s De Wallen, there are almost no children at all and you can imagine if you close your eyes that they don’t even exist. For many of my friends they don’t. There is an invisible divide between us, I think, those of us who have had children and those who haven’t, and I think we both feel pressured in different ways. When my third child was born, a colleague asked me why I had decided to have one more. “You will never be able to support them on a journalist’s salary,” he said. He was right, but in my mind, that was somehow irrelevant. I took the whole thing to be a kind of godsend or the fulfilment of a prophecy. “Did you expect me to weigh the pros and cons, make an Excel file, and budget for it?” I asked him. “Yes,” he said. “Of course!”

He’s never had any children and so the world of having children was still abstract for him. As it has been for other childless friends, who seem to see kids as something like larger pets, that you can leave at home with a bowl of water for a day or two while you head off to some soiree. Children are an impediment to having fun, a thick wall that walls off happiness. “Every guy I see with a kid is walking down the street, shaking his head and talking to himself,” another friend told me. He hasn’t had children either.

The world for parents among childless friends can be a cold one. “Aren’t you coming to the party?” someone might ask. And then they are disappointed when you can’t, because your daughter is vomiting. They understand that such are the pitfalls of reproduction. They can’t see why someone would voluntarily do it to themselves. Where’s the benefit? Truth be told, it makes no sense. Because if I was to weigh the pros and cons, it would never be the right time to have children. The forces of Western society seem aligned against it. They make it hard in every way.

The West’s days are over, it seems. There’s nothing to do but close up shop, turn out the lights.

But if the ship of the West is sinking into the sea, why not just get our kicks before it slips below the surface?

ON MY LAST NIGHT in Amsterdam, I take a walk to see an old friend. She lives all the way at the end of Vondelpark, which is where my hippie father spent a night sleeping on a bench in 1973. I think about my father as I walk the avenue beyond Leidseplein, which is lined on both sides by restaurants and homes where childless couples watch Netflix while the West slowly dies. In one of these apartments lives an my friend from New York who, like me, attended college in Washington, DC, and later settled in Europe. She has married a Dutchman and has made two Dutch children who are now awaiting Sinterklaas.

Their building is a brutalist masterpiece. Its balconies face an internal courtyard. Outside the doors to the apartments, some boots and toys can be seen. Families have started to move in here, replacing the first generation of inhabitants who had lived in it since it was built in 1961.

That was the year the Berlin Wall went up brick by brick. The next summer, the Cuban Missile Crisis happened. Life must have seemed just as impossibly damned then as it does now. Yet people continued to marry and have children. In 1961, the Netherlands experienced the highest birth rate in recent history, with 3.2 children per woman. But just like in Estonia, the Netherlands are expected to lose people over the next decades. In this massive post-war edifice, young families huddle. They are demographic survivors.

My friend’s family gathers around a table and eats soup and pasta. The little boy, aged three, is dressed in pajamas that resemble a cat. The girl, aged six, is eager to put out her shoe for Sinterklaas, who will reward her with snoep, or candy. My friend’s Dutch life is very different from my Estonian life. She lives in the busiest corner of Europe. I live in the frozen wastes. But we both know the joy of setting out a shoe or slipper for a Christmastime visitor who brings candy.

The family tonight is being visited by a neighbor, a 34-year-old Dutch designer who looks like a woman from a Johannes Vermeer painting. She has red hair and is milky white and once lived in a black neighborhood in Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn where her neighbor was in a gang. In Amsterdam, she has taken up with a Russian software engineer from Saint Petersburg, and they are expecting their second child. “I only have a few months left,” she says, patting her belly.

This is how new Europeans come into this world.

Later, when I ask my friend about why she decided to have children when so many of our classmates didn’t, she gives a bunch of different reasons. But she also notes that it hasn’t been easy being a mother, that her career has suffered and that academia, even in the progressive Netherlands, is still quite male dominated, and that the women who have secured the best positions for themselves tend to not have children. But she does love her children and she wouldn’t have it any other way, she says. Her main reason for having children appears to have been that she had an awesome amount of love to give and just wanted to give it to someone.

Which, to me, seems like the best reason that a person can have.

EVEN LATER THAT NIGHT, I head back to the Red Light District. Something fascinates me about its stark grotesqueness. I lean up against the Oude Kerk, which has stood since the 13th century, writing in my journal with the hope that the walls of the church will imbue me with more marvellous writing powers. Down the way, some young men negotiate a price with a sex worker. Then I go looking for the woman I saw on the first morning in Amsterdam, the lady in the window. I just want to see her one more time, to wave goodbye to her, to make us both feel like we are human, for just one precious moment. The West may be rotten to its core and in decline. We may all peer out at our futures with that same haggard look of resignation, but I do feel compassion for her as she plies her trade. We are, after all, in the same kind of business.

An Estonian version of this article appears in the winter issue of Edasi magazine.