I MUST HAVE RENTED an apartment from a middle-aged Estonian man. He was maybe a decade older, dark tufts of hair, graying at the temples, tawny complexion. He might have been Spanish or Jewish in a previous life. He worked in some dusty corner of the financial services universe and was always dressed smart casual, with a jacket, shirt open at the collar, khakis.

His wife had recently left him, or they had separated or taken a time out. So they said. She took the rest of the children off to the Canary Islands, where she had become a poolside yoga teacher and worshipper of the Hindu love gods. The eldest daughter stayed behind to finish her studies. She was disarmingly beautiful. He was certain the girl had caught my eye. She had.

At night, her father would kick off his loafers after a long day spent shilling for the bank and watch the news on an enormous screen he had got a great deal on during the pandemic. When he saw me entering my apartment through the big glass windows on the first floor, and most of the house was made of metal and glass, he would shake his head a little and purse his lips and then nurse another sip from a bottle of beer. The apartment itself was a tranquil single room, wide and spacious, all painted white, with high, echoey ceilings, and a small kitchenette.

It had three windows and through them I would watch the eldest daughter arrive and depart on her way to or from her semiotics classes. The bob of a golden brain in the late winter sun. The lyrical cadence of a youthful, ever optimistic voice heard through the glass, concerned for her joyless, dead-hearted father. There was something to her, a kind of music so faint you could only hear it if you strained your very ears. But it was also so removed from my waking conscience that I could barely grasp at it, even if I tried. This sparkle might have found its way into a magazine article I wrote, one with sultry allusions to such inappropriate relationships.

And then one day, my landlord was there before me, clutching a rolled up copy of the magazine’s latest edition in his hand, ready to strike. I could see my face above the column, which was printed neatly in black and white “You,” he said, “are a sick pervert! I have already initiated legal proceedings, a kohtuprotsess!” I stepped back and he whacked me with my own words. I tried to defend myself. “But it was all fictionalized!” I cried. “All of it was fiction!” “Lies,” he shouted and struck. “Of course, some of it was based on reality.” “Jail!” he growled. “Jail!”

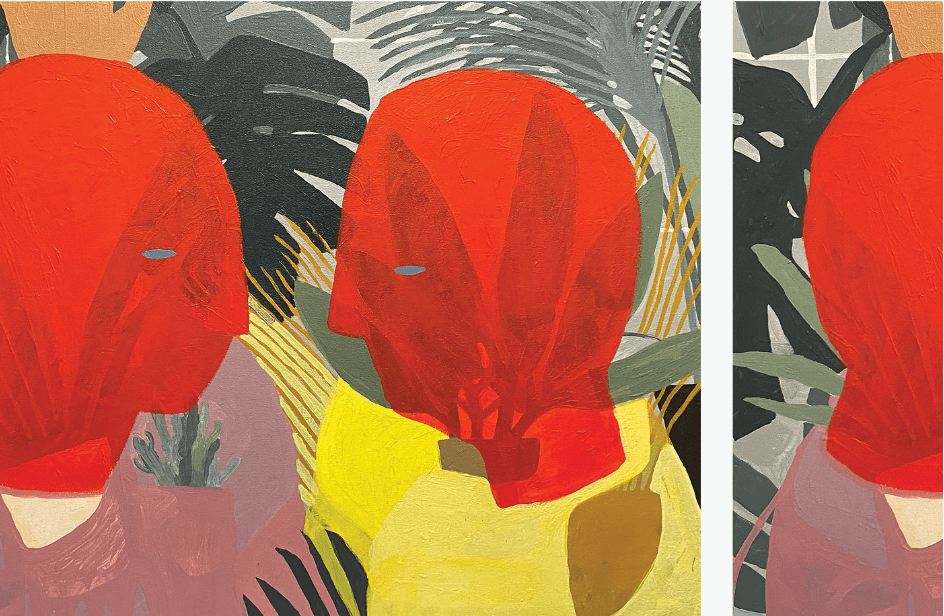

In my apartment, I let down the white blinds. Outside I could hear him howling, banging. I grabbed my things, crawled out the back window like a character in a Willie Nelson song. Then I was down the forest path, on my way, almost free at last when his wife appeared like mirage. I tumbled and there were orange leaves everywhere, so many leaves I began to swim. The enlightened landlord’s wife looked down out me, her head wrapped in a bandana. Stars flooded the sky and began circling her like little birds. They arranged themselves into a crown. She reached down and pulled me free from my leafy oceans. At long last, I had been rescued.

The landlord’s wife was a fine looking woman, very smooth features, a kind of gray-brown hair just visible beneath her turban, and she had very clear blue eyes that were skies unto themselves. She did not fear my love of her daughter, for as she saw it, all daughters needed to be loved. “Would you like honey too?” She poured me some tea on the terrace later. I mixed in the honey, watched it dissolve in the peppermint, and drank deep from the warm ceramic cup. I was still kind of shaken up and could see her husband through the windows. He was filming the whole thing. Evidence to be used at trial. He gave me the middle finger. Then he motioned to his throat and made a slashing gesture. He mouthed the words: “Pervert, pervert. Jail, jail.”