BEFORE I GO ANY FURTHER, I should tell you more about Montrone and Canneto, these two towns outside of Bari that have grown together. For centuries they remained apart, distant, at arm’s length, and in fact they maintained two very different dialects. One of the towns hosted a Norman French garrison in the 11th century, and its dialect was therefore influenced by French. The other was settled by Greek refugees in the 10th century, and its dialect was infused with Greek. Cousin Lorenzo says it’s possible to tell someone from Montrone, a montronese, from someone from Canneto, a cannetano, by the way they say the word for “bread.”

“They say, u pan,” says Lorenzo. “But we montronese say u pen.“

The official word for bread in Italian is pane. In French, it’s pain. So the local dialect word, which is common in the dialects around Bari, called barese, is a bit closer to French. To me both of the versions sound almost exactly the same. U pan, u pen. U pen, u pan. U pan …

There are these tiny differences, you see. But a single vowel can give away your identity.

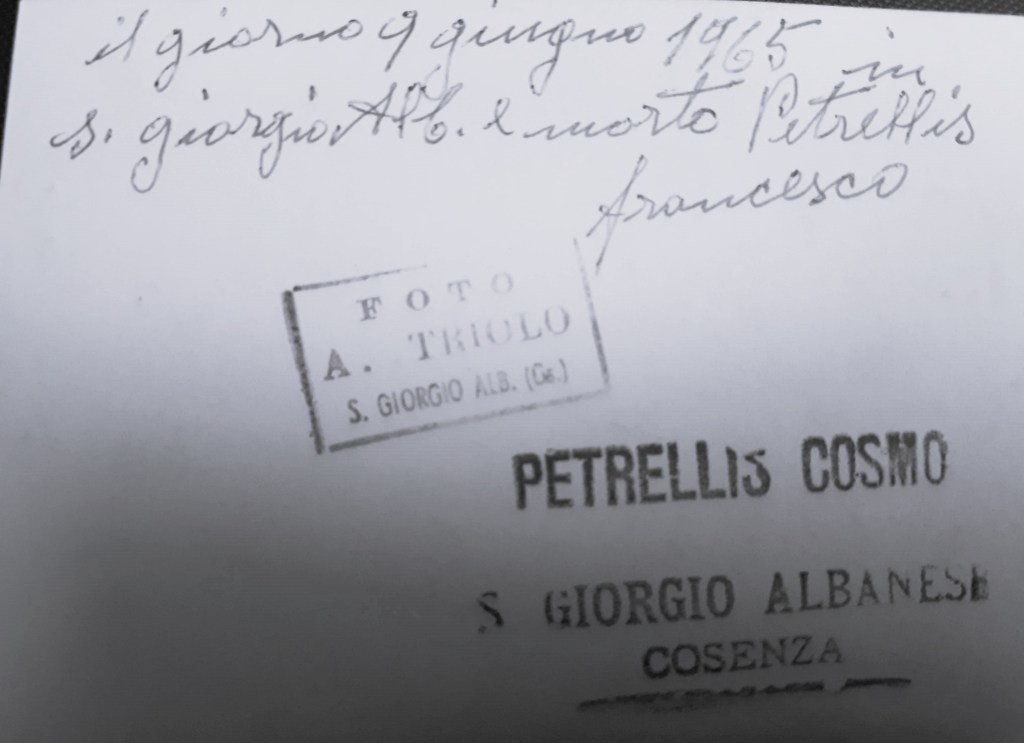

One must realize that the country or nation of Italy is largely a fiction, or at least a coincidence of geography. Every region, every city, every town, even every neighborhood has its own history and its own dialect, many of which are so unintelligible to outsiders that they are considered their own languages. It is said that the singer Frank Sinatra’s mother, Natalina, who played a role in local politics in Hoboken, New Jersey, where Sinatra was born and raised, was successful in part because she could speak all the dialects of the Italian peninsula. This made her indispensable when dealing with the immigrants who thronged New York City a century ago, people like my great grandfather Domenico Abbatecola, who was from Bari, or my father’s grandfather, Salvatore Petrone, who came from a village in Calabria. Even during my first trip to Italy, at the age of 22, I became aware of the language issue when I was stopped by an older man with a white mustache from Palermo on a street in Bologna. He was looking for the train station. People had responded to him in the Bolognese dialect. He was unable to understand their directions. “I can’t understand a word these people say,” the old Sicilian told me that day.

How odd then, that I could understand him. When I was 22, I really didn’t speak Italian at all.

Now and then I replay that moment over and over in my mind. How did I understand him?

***

FROM THE PORT OF BARI, where the ships leave for the ports of Bar in Montenegro, Dürres in Albania, and Dubrovnik in Croatia, it is about 15 straight kilometers south into Montrone and Canneto. These towns, however, no longer appear on maps because in 1927 they were united into one municipality called Adelfia, from the Greek word αδελφός (adelphos), “brother.”

On a map, at least, the Montrone and Canneto sections of Adelfia are distinguishable. Canneto, to the west, with its ancient Torre Normana, or Norman Tower, is the larger of the settlements. Montrone is the sleepier, eastern side of Adelfia. The main landmark here is the public gardens, with its Fontana dell’emigrante, or Fountain of Emigrants, which is a fitting name because my great grandfather Domenico was born and grew up right across the street.

Just a few houses down, there is a little cafe called the Pasticceria Caffetteria Petrone, where you can get a pastry and an espresso in the morning. There is nothing better than waking to the sounds of the church bells, or to the neverending calls of the people in the streets, and walking to the Caffeteria Petrone. The owner, as far as I know, is not a relative, and is from Naples. There are many Petrones in southern Italy, and we are not all close relatives. There, you take your place at the counter, and wait for that little white cup to arrive. Everyone is here, the dentist, the postman, the cosmetologist. And even if they don’t know you, they still know you. The eyes search each other, the cup is lifted, and you are wished a buon giorno.

“Good morning,” or, actually, “good day.”

This is how the montronesi start their days, and just a few hundred meters down the Via Vittorio Veneto, and over the old aqueduct, the mornings of the cannetani are much the same. Only that they call bread u pan and the montronesi call bread u pen. There are other divisions. For example, no one in these two towns can agree on exactly where the border between them lies. This I was told one night, strolling around with cousin Lorenzo. While the aqueduct seems like a natural boundary, only the people from Canneto believe that. The montronesi say the boundary between the towns is really a column on an old building just over the bridge. “This is where Montrone really ends,” said Lorenzo one night as we paraded around the old lanes of Montrone, venturing into disputed territory. “Beyond this point, they say u pan and not u pen. Beyond this point, you are dealing with the cannetani, who speak a very different dialect.”

He gestured quickly with his head, as if these people, the cannetani, were an alien race.

***

I DON’T KNOW how old my Italian cousin Lorenzo is, and I have never asked, but I assume he is about my age. At the time we first met, he was working for a software company that designs platforms for managing airports. He had returned to Bari after many years in Rome and he was single and had decided on something of a career change, to go into academia after a life in the private sector. I cannot fully understand how the Italian economy even works because I only see these people eating and meeting with family members, but during the working hours, they do disappear someplace, to do at least some work, just a little, before returning to the table.

Lorenzo’s father, Giuseppe, works in agriculture, a job he quite enjoys. In the evenings, he heads out to the piazza in Adelfia to play cards and share stories with old friends. Night after night, the old men are out there in their caps talking and making noise. At night, Italy is even livelier than during the day and I am always impressed to see the offices of the country’s political parties on the piazzas in the evenings, the windows lit up, and people seated around inside eating pasta together. They are more like social clubs than real political parties. In the US, they would be outside with signs, yelling at each other. In Adelfia, the only thing they yell is something like, “Would you please pass the bread?” Or, “How about another espresso?”

Lorenzo against this backdrop casts a more lonesome, stark figure. He is tall, dark-haired, at times silent, at times with great humor. He is instantly likeable. Some people just have this kind of quality. You can’t help but like them. While his career path is in mathematics and science, he loves to talk about traditions and he is very thoroughly grounded in the local culture. That same night we went out to see the disputed border between Canneto and Montrone, we also stopped into a church to light a candle and view the shrine to San Trifone, the patron of Adelfia. The interior of the Church of Saint Nicholas of Bari and Saint Tryphon Martyr is beautiful. Its high ceilings are covered with pastel blue and frescoes, triumphant angels, and nativity scenes. And beneath all of this color moved a figure clothed in black named Lorenzo.

I cannot say that Lorenzo is a nationalist, because how could a montronese belong to a nation? Italians are not a nation in this sense, they are a combination of many now forgotten peoples, mingling on the soils of this land over generations. The Greeks, the French, the Albanians, the Visigoths. But Lorenzo is proud of the south and of his home here in southern Italy, and is sensitive to the stereotypes about the southerners that pervade Italy, and elsewhere, that they are dangerous, criminal, and violent. He also likes to talk about history, and how Bari and adjacent areas of Italy were sacked and plundered by foreign armies. In the 9th century, Islamic invaders created the Emirate of Bari, but just a handful of years later the Byzantines took it back from the Ottoman Turks. Then, in 1071, Robert Guiscard and his swashbuckling Norman adventurers swooped in. Among other feats, they built the Norman Tower right here.

Not only the tower remains, but the blue eyes and light hair that exists to this day among some of the inhabitants of Adelfia are a reminder of these Normans. My great grandfather Domenico also had blue eyes as does my mother Christine. As do two of my three children. As a child, it linked my mom and her towering Italian grandfather. He would look down and say, “Our people came from the north.”

“For centuries, Italians were subjected to invasion after foreign invasion,” Lorenzo told me that night. “Only in 1860 were we able to stop being picked apart and fought over by others. Then came the risorgimento, the unification under Giuseppe Garibaldi. Some say that it was a unification, but others say that the piedmontese just annexed the rest of Italy. They helped themselves to the resources and labor of the south, but they think that we are criminals.”

“But my grandfather Petrone, my father’s father, said that our people were criminals,” I insisted. “I have heard that Calabria, where the Petrones were from, was legendary for its banditry.”

“No, no the Calabrese weren’t bandits,” said Lorenzo. They were briganti. Brigantines! They were a movement, trying to wake up the north, to tell them what was going on in Italy.”

Such were the lectures of my cousin Lorenzo. He seemed offended that I would even suggest that our countrymen were anything other than noble Robin Hoods, stealing from the rich to give to the poor, fighting the powerful and wealthy families of the north by flouting their laws and creating their own codes of justice. One man’s brigantine was another man’s criminal. His body language was subdued though. Lorenzo is not your stereotypical Italian who argues loudly, flailing his arms. It’s hard to imagine him yelling out a car window while pounding away on his horn. But in his quiet certainty about the nature of Italy, I felt I had said something wrong, even though I was proud of these stories of criminality that we had carried with us from the south. In America, such tales of lawlessness had a kind of mystique. Who wanted to descend from law-abiding Italians, when you could claim your cousin was a notorious outlaw?

“People are afraid of the south,” I pressed on. “A Florentine told me it’s dangerous. They say they lock their cars when they see Neapolitan license plates. Even when they are driving.”

“Florence is far more dangerous than Bari,” my cousin Lorenzo shook his head. “That’s what’s so funny about the northerners, you know. They think the south is full of criminals. But since all the money is in cities like Milan, that is where all of the real criminals go. Milan is more dangerous than any city in the south.” To his credit, nobody robbed us that night as we paraded around Montrone and Canneto in the dangerous south of Italy. The only thing I was ever robbed of in the south was hunger though, because it seemed like all we did was eat.

***

SOME DAYS LATER, we had a fine meal at a restaurant in Adelfia, consisting of tiny mozzarellinis, polenta baked in marinara sauce, and many other delights, such as sauteed chicken hearts. Lorenzo was there, as were Pamela and Antonella and Lello. Platter after platter of food arrived, glasses of wine were consumed, and I began to worry who would be picking up the bill for this feast. There was even a mozzarella the size of a loaf of bread. On the way out, I asked the chef at the counter about the bill. I imagined that it was enormous.

He in turn simply asked me if I preferred Northern Italy or Southern Italy.

“Whose side are you on?” said the chef. He was a roly-poly man with Sinatra blue eyes.

“The South,” I told him with my most casual Italian shrug. “Naturally.”

“Good! In that case, your meal was free,” the chef said and bowed his head. “Grattis.”

Much later, I found out that my cousins had already settled the bill. But I like to live in that illusion that just professing a love for the South over the North could earn you a free meal anywhere south of Rome. All you had to say was that the South was better, and a waiter would bring you a tray of free mozzarellinis and the cooks in the back would start baking polenta.

Who knows. Maybe it is true.