SOMETIMES I WONDER how I ever wound up here. This northern land of trees where there’s snow on the ground from November through April. The Estonian doctors told me long ago that my body wasn’t designed for this climate. I have come to believe them. My body was designed for sun-baked countryside, for almond and olive groves, for the spray of the sea and for tins of tuna fish. But I am not there, where I should be. I am here and it is snowing again.

Such thoughts ramble through my mind as I make my way to an establishment called the Grand Hotel. There’s a gym in the basement there and you can book it for an hour at a time. That small hotel gym basement has become my sanctuary in the winter months. Outside, it’s dark, freezing, but down there it’s warm and I can wear shorts. There’s also a TV mounted on the wall. My favorite channel is the history channel. It almost exclusively shows documentaries about Hitler and Mussolini. Sometimes the old film reels of Mussolini bother me. I look like some of the blackshirts crowding around Il Duce. There’s a cranky old Estonian man who gets coffee at the same cafes that I do here, and he refers to me as one of the “Mussolini nation.” “What are you doing in Estonia?” the old man asks now and then. “You’re an invasive species!”

***

THE CRANKY OLD ESTONIAN MAN, whose name is Imre, and who also sometimes visits the hotel for late night and early morning coffees, isn’t here this time, but Ragne is at the desk as always. Oh, Ragne. Ragne is about five years younger than me and has declared her singular interest in older men. We’re just so mature and worldly. She likes to wink at me, fluster me, to toy with me, and then tell me that she has absolutely no interest in me. She is a serious Estonian woman, who prefers serious Estonian men. A sentimental Italian is of no use to Ragne. She plays with her blonde hair. Life is better as a blonde, Ragne says. Ragne has a new manicure every other day. She also always has to remind me to be on time. She has to remind me because I often roll in 10 minutes late. Not on purpose. It just always happens that way.

Ragne finds my tardiness infuriating. This time I have decided to book my gym hour for 5 pm.

“That means 5 pm Estonian time!” Ragne calls out to me as I walk back out the door. This somehow gets under my skin, strikes at my very identity. 5 pm Estonian time. Invasive species. One of the Mussolini nation. How did I even wind up in this land of snow and no nonsense?

“But didn’t you know?” I call back. “Time doesn’t really exist. It’s just numbers!”

“That’s not true,” Ragne shouts back over the desk. “Time does exist.”

“No, time doesn’t exist, Ragne,” I reply, giving her my best Italian shrug. “Time is crap,” I say.

Then I leave.

***

I DECIDE TO HEAD DOWN the street to the café for an espresso, Ragne’s words nipping at my heels like little dogs. If I’m not operating on Estonian time, I must be operating on Italian time, I think. And Italian time, as I have noted, is flexible. Italian time is so limitless that it doesn’t exist. Whole years can disappear into seconds in Italy. Seconds erupt forth from years. The idea that you could be late for an appointment is surreal, absurd. Do you think Fellini was ever late for anything? Fellini was always on time, because whenever Fellini arrived, it just happened to be the right time to arrive. Life does happen, you know. Life has its own plans. You don’t know what might happen in life. Here I am reminded of a story about my great uncle Vinny, who was the older brother of my mother’s father Frank. This happened way back in the 1950s or 1960s, before the era of smartphones, a time when one picked up the receiver and said, “Give me New York 555,” and a dispatcher connected your phone line to another one. As my Estonian cafe espresso arrives black and hot, I think about the story about Vinny and time.

It goes something like this.

***

ONE DAY, my mother Christine, then maybe an adolescent with a soon-to-be very dated permanent hairdo, received word that her Uncle Vinny and his entourage of wife and six children were on their way to visit her father Frank, and that he intended to be there later that same morning. So she put on her best white dress and went outside to sit on the stairs and to wait for Uncle Vinny to show up. It was a fine summer’s day and somewhere the Four Seasons were probably playing on a radio. Frankie Valli was singing. My mother was waiting patiently.

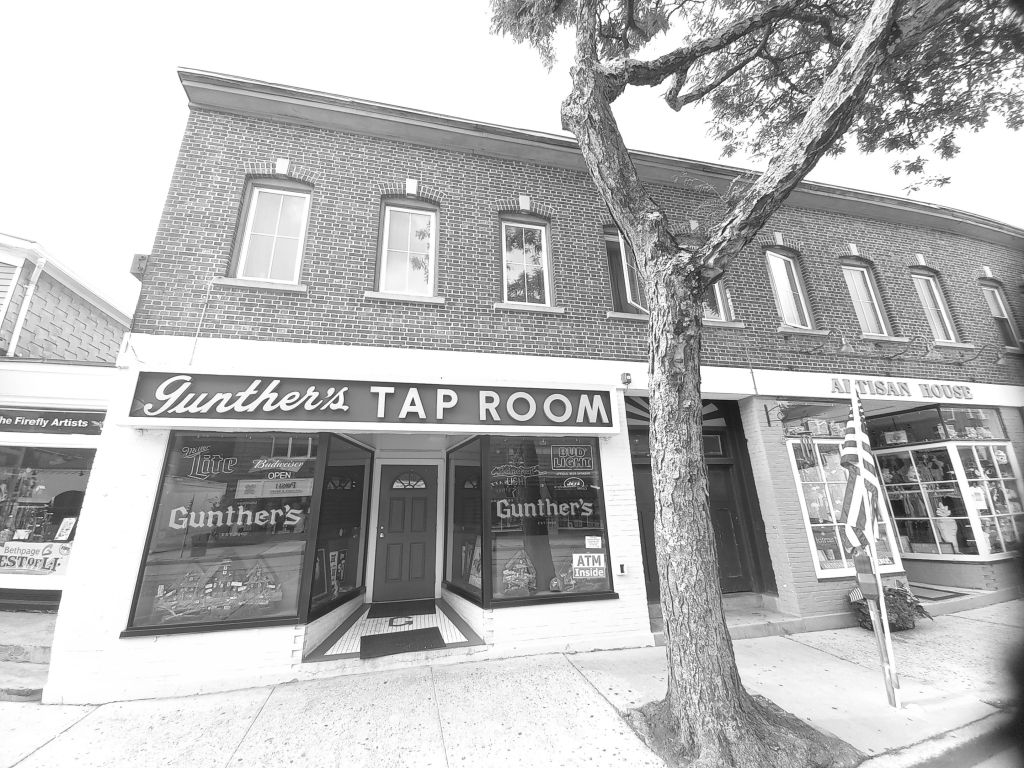

Uncle Vinny operated a restaurant on the south shore of Long Island, which is the largest island in the United States and juts out into the ocean east of Manhattan. Like New Jersey to its west, Long Island became a sandy, coastal destination for Italians longing to escape New York City. They moved there and built their homes, their children went to school, and within a few years, they became new Long Islanders, living side by side with the original British stock, happy to live in such a fragrant place. The name of Vinny’s restaurant on Long Island was “Vinny’s Happy Landing.” It was from this beachy enclave on the south shore that Uncle Vinny was traveling in his bid to make it to the north shore of Long Island to visit his brother Frank, who lived in a New England-feeling coastal village clustered around a harbor called Northport. My mother was there waiting for him to arrive in the morning, sitting outside in her dress.

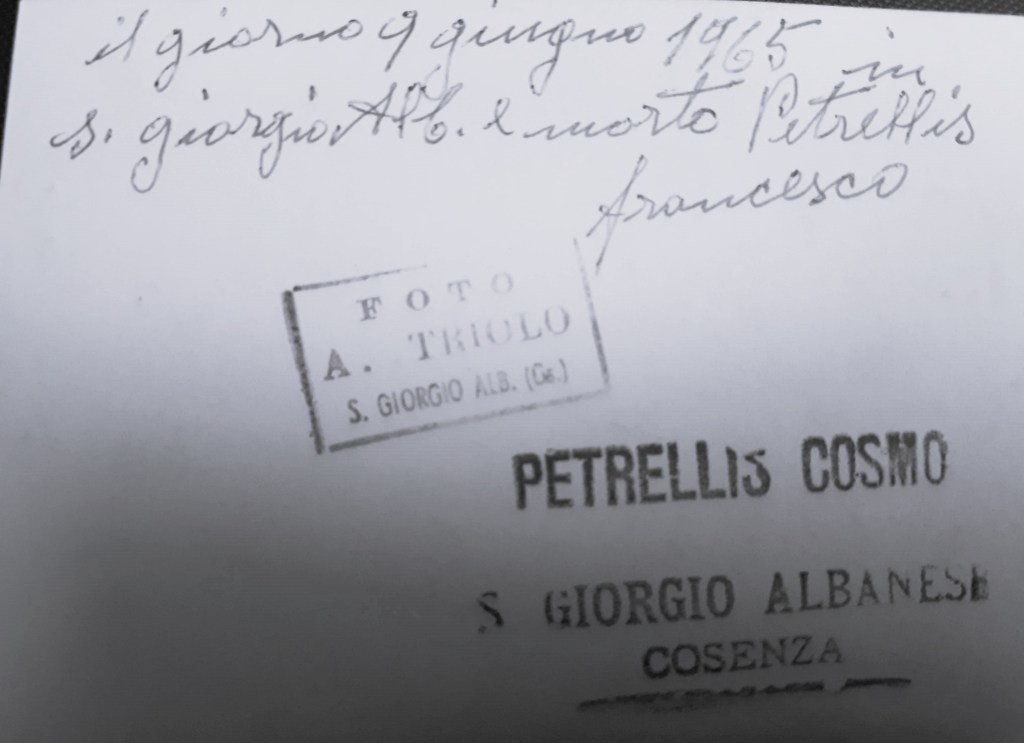

I’ve only seen one photo of Vinny as a young man in the 1940s, but I could immediately recognize the slant of his eyes and white-toothed smile, finished off with curly-black hair on top. He seems to have been quite charismatic, and I can imagine my mother waiting for this man to show up that morning, maybe even with a gift of some kind, or perhaps a bouquet of flowers. But Uncle Vinny got distracted along the way. Maybe he had some car trouble, but more likely he ran into some friends, and got invited over for coffee or something like that. Then he met another friend who offered him a quick lunch and, as you know, it’s impolite to refuse a meal. Morning turned to noon. Noon turned to late afternoon. My mother kept waiting. The Four Seasons were no longer playing. Now it was maybe the Everly Brothers. Afternoon turned to evening. The crickets began to chirp. My mother was still sitting there. All day long she waited for the magic uncle to make an appearance, but Uncle Vinny never came.

***

THIS SAME GIRL grew up to be legendary for lateness too. It was a joke in the family that if a party started at 4 pm, it was best to invite my mother at 2 pm. That way she would show up two hours late and be right on time. I must admit, I have inherited this carelessness about time when it comes to being anywhere, even if it is for my own time at the gym in Estonia. Of course, I only allow myself to be five or 10 minutes late on those occasions, and I do make it to flights mostly on time, even though I always feel a little annoyed by punctuality and the rigidness of the non-Italian world. People are late because the fates of life interfere in their schedules. Can one always prepare himself for every flat tire or broken-down train? What if someone asks you in for lunch? Would you really refuse? But it is an insult to refuse lunch.

Wallowing in my wintry blues in Nowheresville, Estonia, I think about such things. Other people talk about the weather, real estate, or the soaring prices of cappuccinos, but I am still contending with Ragne’s pronouncement that I should turn up on “Estonian time” and not a second too late or too early. What is it with these Northerners and time? I often wonder what it is they are running from here, or trying to accomplish. How great is the fear of these numbers on the wall? Don’t they know that time is elastic? I understand, at least logically, that the hotel here needs to manage its gym appointments. I am never dramatically late. I don’t show up in the morning or the evening. But five minutes? Ten minutes? Come on! Is it really such a sin to be late? What happens to you if you are not on time? Do you burst into flames? Sometimes I like to be late, honestly. I feel that I am slowly teaching the local people a lesson about the futility of clocks. They need to learn such things and I am here to teach them.

***

A FEW YEARS AGO, when I was in Bari, a coastal city on the Adriatic and the ancient home of my mother’s family, the Abbatecolas, my cousin Michele told me he would be at my rented apartment at 5 pm. Michele’s grandfather, also named Michele, and Domenico, the father of my grandfather Frank and his ethereal brother Vinny, were brothers. As such, Michele and I are rather close relatives and treat each other as such, with the obligatory pecks on the cheek.

From there, Michele would take us to dinner in Adelfia, about 15 minutes or so from downtown Bari. Being a somewhat dutiful resident of a Northern European country, I made preparations just in case he might actually show up at 5 pm. But true to his nation, our special “Mussolini Nation,” Michele did not show up until about 6:30. There he was, standing outside my apartment, holding his phone, waiting for me. Italians are often stereotyped as being short people, but Michele is as tall as I am. He has great gray hair, wears glasses, has a patient manner and friendly smile, and is anything anyone would want in an Italian cousin. Michele himself is about 15 years older than me. He plays guitar in an REM cover band, and sometimes I have helped him make sense of Michael Stipe’s muddled lyrics. This is not an easy task for me either.

And so there he was. He was also an hour and a half late, and yet didn’t even bother to acknowledge it or to apologize. I didn’t ask him any questions. We were on Italian time that night and Italian time felt great. Italian time was wild and unstable and truly exciting. You never knew what might happen on Italian time. That was part of its everlasting allure and fun.

***

DURING THAT SAME TRIP, my 10-year-old daughter Anna got frustrated with living a humdrum existence in a rented apartment around the corner from Bari Centrale, besieged by scooter traffic in the mornings, while her father downed espressos in little dive cafes and engaged in meandering conversations with relatives in Italian at night. To calm her need to do touristy things, I rented a car from a firm near the central station and took off across the country to the famous Pompeii. There she saw the fossilized remains of Latins who had given up the ghost in AD 79. She was so impressed by the ruins that she posed for photos by the stone corpses and we drove back to Puglia happy. “My classmates will be so jealous,” she said.

On the way back though, we were impossibly late to return the car. There had been an unusual snowfall — it was November — and just getting past Salerno was a slippery nightmare of traffic jams and cursing drivers. The renter, a short, scrappy, amiable fellow who had once lived in New Jersey and spoke excellent English, had specified a return time of 9 am. It wasn’t until 11 am that we showed up at the agency to return the car. Curiously, the man had stepped out of the office but left the door ajar. I went inside and left the keys. I was expecting him to call me up and demand another day’s rental fee for the late return. That’s what they would do to you in Estonia or in the United States, or other countries run by punctual people. Later, I went back to apologize. It seemed like the right thing to do for my error of returning the car late. The proprietor had just walked back from having another espresso and was in rather high spirits.

“But we were two hours late!” I said. “I am so very sorry. Please forgive me for my late return.”

The man just gave me a wonderful Italian shrug in his leather jacket. “The contract says you had to return it in the morning and it’s still morning,” he said. “Mattina è mattina,” he said. “Morning is morning.”

***

I REVISIT THAT PHRASE “morning as morning” on this snowy morning as I sip my coffee and the flakes cascade and sparkle down. The cranky old man is at the counter now. He’s talking about politics but has not yet come by to speak of Mussolini and invasive species. In Estonia, an easy-going expression such as “morning is morning” is seldom heard, I think. Up here, things happen on Estonian time, which can be as ruthless and unforgiving as the weather. Up here, people fear clocks. Down Italy way, nobody looks at them. In Italy, morning is just morning.

I remember that morning when I returned the rental car in Bari late. I remember how I paused to look at the palm trees that stand in the park in front of Bari Centrale that special day, so proud and so tropical. There was something so warm and supportive about Italy. It was as if my body had been created from its fertile fields. In Italy, it felt like the whole country loved you. You could talk to a stranger and he would talk back. You could be late with a rental car and the renter wouldn’t be annoyed. You could stand outside in winter admiring palm trees. I had been told that place was not my home. I didn’t speak the local dialect. My forefathers and mothers had left it all behind. But how could it not be home? Maybe home isn’t a place? Maybe home is something that simmers away inside of you like a hot espresso on a northern day.

Maybe home is something you can never lose.