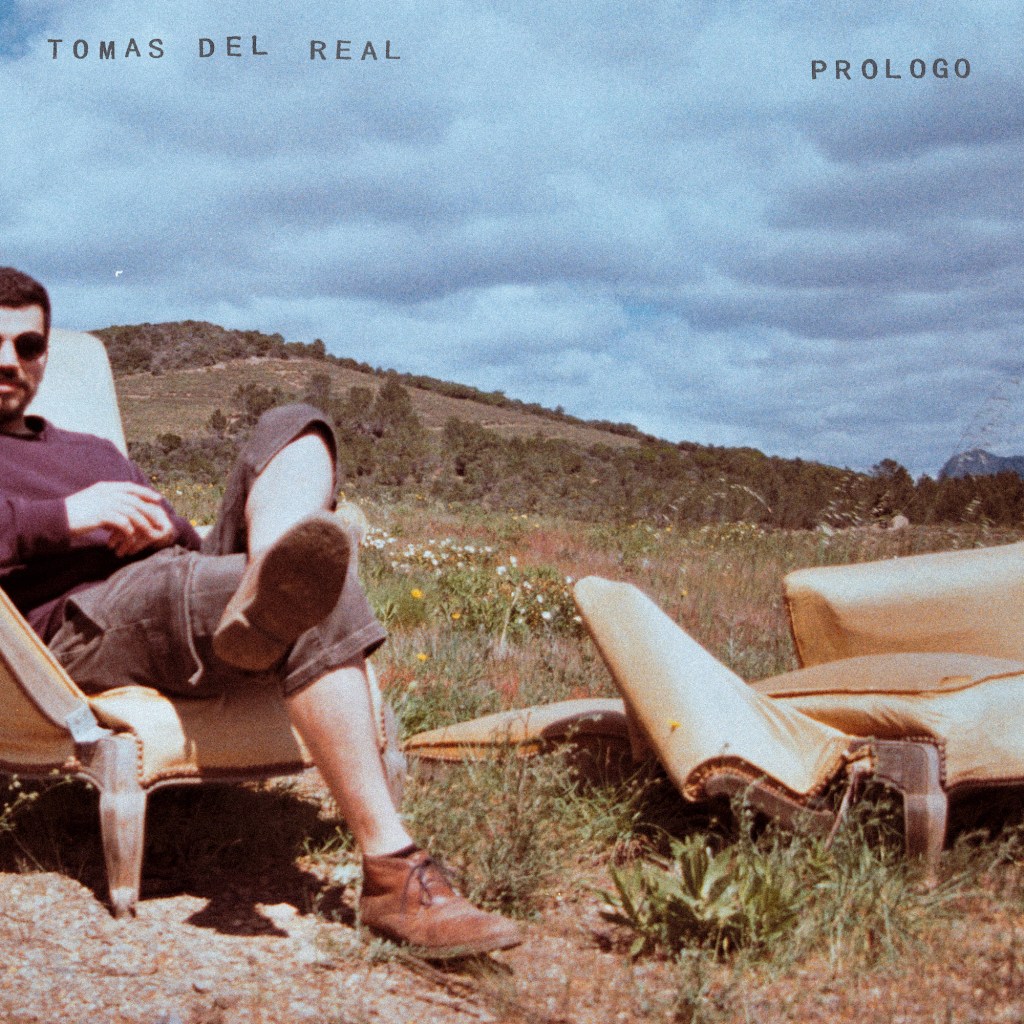

WHAT IS WRONG with the youth of today? The world’s on fire, the clock is ticking, and Tomás del Real is hanging in backyards from Canada to Estonia, tinkering with his guitar, jamming with fellow travelers and otherwise observing the downfall of civilization coolly from behind his sunglasses. Even the cover photograph for his single “Prólogo,” released last August, shows the chill Chilean in media res, as if he was caught off guard while he was contemplating something more profound. He looks like a Latin Sigmund Freud, I think, one who just survived a natural disaster because there are broken couches around. Maybe that’s exactly who he is.

While listening to the entirety of the album Notas Rotas, I hear many interesting things. Released in the dreariest days of late November, it has a warmth to it. The opening song “Prólogo” is a burst of warm air, propelled by the violin of Alan Mackie and flute of Katariina Tirmaste. Right up front, this record promises something that food critics might call fusion cuisine. There’s del Real’s contemplative, Tropicalia-laced meditative poetry and innovative melodies coupled with what sound like North American and Estonian influences and driven forward by a thunderstorm rhythm section of percussionists Magnus Heebøll Jacobsen and Steven Foster: the former from Denmark and the latter du Canada.

On the cover of the album, they all look like a bunch of farmers who took some time off from the harvest to fashion 10 incredible songs, and then went back to messing around with a tractor or something. But there was a method to this folk madness for del Real is the consummate artiste.

“In every album, we try to shape and find the reason and the language in which the songs exist,” remarks del Real. “There were a couple of musical languages that were present in the picture.” In the case of ‘Prólogo,’ Alan Mackie, who also played bass on the record, was a co-composer and co-producer of the single, as he was on many of the album’s songs, bringing along his own sentiment (Mackie is from Prince Edward Island). In combining with del Real’s own Latin American folk, they have created a blend of music they jokingly refer to as LatinAmericana. But there are Old World influences too.

“There are a lot of European folk influences, such as Eastern European uneven time signatures,” says del Real, “which we tried to implement in a very organic way, and some Scandinavian influences, both in the percussion and in different colours in the instrumentation and arrangement.”

While del Real wrote the songs on the album and the record is credited to his solo project, it is very much an ensemble effort and grew out of an ongoing collaboration with Mackie and Tirmaste. Mackie and del Real even hit the road and toured Asia at the beginning of their co-sojourn, with dates in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. “I had a bunch of songs waiting to be something and we decided that could be a good place to try them out,” says del Real. “From that experience we started to shape where the sound was going and it felt very natural to start working on this.”

Katariina Tirmaste was “another fundamental pillar” in the creation of Notas Rotas, helping to flesh out the compositions and to arrange them. Del Real credits her as a “creative and emotional performer,” one of who provided sensitive, flexible parts to the different songs that eventually made up the new record. “She’s incredibly versatile and also without taking up more space than needed, which is a very humble and Estonian approach in my opinion,” he says.

The record itself was put down in home studios in Toronto, the south of France, the west coast of Sweden, not to mention a multitude of closets in apartments in Estonia. From this pastiche of on-the-fly audio recordings, a sound engineer of fortune called Jorge Fortune in Patagonia mastered the sonic tapestry of Notas Rotas, which is that rare record that sounds good whether it’s been played in the car, through headphones, or on your smartphone.

I know because I have tried listening to it in all three environments. These recordings hold up.

Del Real I have known as a musician for years and have attended his shows, including some with Tirmaste and Mackie. While I hesitate to say anything about his songcraft, I can say that some of the melodies on this album challenged me and required multiple listens to fully digest, which for me, as a listener, is the mark of the very best music. Having a minimal knowledge of Spanish, even after years of instruction in high school, his lyrical intent remains a mystery to me. In his own words, it reflected the transient nature of his life as he moved around as well as the emotional winds blowing through. “It had a lot of reflections around inconclusive situations, self-awareness, letting go, and letting life take its course,” del Real says.

He was also demoing the material on the road and in front of his fellow musicians, which took him out of the more introverted, isolated settings that fueled the creation of his last album, Principios de Declaración. Solo albums can be complicated territory for any musician, though del Real is a singer songwriter and thus a solo artist by default. With Notas Rotas I am reminded of David Crosby’s solo outings, particularly his first venture, If I Could Only Remember My Name, recorded at the very dawn of the singer-songwriter era in 1971, which saw a whole cast of characters join Croz in the studio (there’s even a cut with Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead paired with Neil Young and Santana drummer Michael Shrieve).

While Croz’s musical influence might not be immediately apparent on Notas Rotas, his spiritual influence is everywhere and I think, might he have lived a little longer and heard the record, he would have approved. The kind of camaraderie that fueled Croz’s effort can be seen here, because these fellow musicians are del Real’s confidantes and he trusted them with this music.

When this album was first released, del Real encouraged listeners to post their favorite songs. But what I have found upon multiple listenings is that my favorite track changes with each listen. Today, on a snowy January day, it is the sixth track, “Distracciones” with its vibrant fiddle parts. Any one of these tracks is sticky enough and interesting enough to catch a listener in its web. Perhaps “La Primera Nieve” or “The First Snow” is the most appropriate for this colder season. And then there is the finale, “Los Sueños” (which can be translated as ‘Dreams’ or ‘Visions’) which is carried along by lovely backing vocals like a ball being carried away upon the waves.

There is, whether it exists or not, and whether intended or not, a maritime fluidity to this music.

For del Real who, like the writer of this review, calls Estonia home, it was this seabound country that most manifested itself in this latest work. It found its ways into its lyrics, its melodies, its colors and moods. “Personally I think it’s very inspired by Estonia, its pace and imagery,” del Real says. He also sees in it a breakage with his past, or the path he was once on, and a fresh intimacy that he credits with producing its raw, unfiltered, and, I would add, touching result.