WHO IS YOUR FAVORITE WRITER? Or who has been the most important writer in your life? People have often asked me this question. My answers change. Sometimes I say Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote every morning, even when his wife Zelda was in the psychiatric hospital. Sometimes I answer Henry Miller, who dared to write so poetically about the darker side of men and of the world. And certainly Ernest Hemingway haunts me, as he haunts every writer, with his strange, adventurous life story. But honestly, my guardian angel has been to this day Jack Kerouac, the author of On the Road. I see my life through the prism of his life, I understand myself through his books. Jack inspires me. Jack cautions me. I would like to write as well as Kerouac wrote his books. But I don’t want my life to have the same trajectory. I don’t want us to have a shared fate.

***

I was thinking about Jack one summery Saturday morning when I drove to Northport on Long Island. My parents live about half an hour east of there, but my mother is from Northport in part. Northport is a port town or perhaps village, about 70 kilometers from the center of Manhattan. It is drowning in greenery and there are lovely views. It used to be a summer place, to where city people would flee and go swimming. There were women with Victorian Era dresses and umbrellas to keep out of the sun and men in black top hats. You know what I’m talking about. They came from the city by train, to spend the summer by the sea. It reminds me of Haapsalu. But I went by car. When I got to Northport, I met up with some relatives. We went for a walk and told some stories. I’m not in the US so often. It was a nice summer morning and it was nice to spend time with my uncle and cousin and to drink some coffee. After our get together, I typed 34 Gilbert Street into the GPS and headed off in that direction. To get to Gilbert Street you have to take Main Street out of town, then turn onto Cherry Street and then again to Gilbert Street. It was interesting that I had been to Northport maybe a thousand times, but this was the first time I had ever been on this street. The house I had come to see was a white, wooden house, a typical working class house. The same kinds of houses are in Lowell, Massachusetts, where Jack was born. That’s why he wanted to live here, I’ve read.

Jack moved to Northport in 1958. Eisenhower was the president of the US. Khrushchev was the leader of the Soviet Union. Mao was building Communism in China. The Korean War was over and the Vietnam War hadn’t started. Kerouac was looking for a peaceful place that wasn’t too far from New York. He was already famous by this time. A year earlier appeared his most famous novel, On the Road. Kerouac was everywhere. On television. On the radio. In newspapers. In night clubs. He was the Beat Generation’s greatest prophet. A dutiful Catholic, Kerouac brought his mother Gabrielle Ange Lévesque to live with him in Northport. An older lady. Conservative. She had been born in Quebec at the end of the 19th century. Religious. Different. The Cold War was at its height and Kerouac hated Communism. He was, at his core, a Catholic, regardless of the fact that he did not exactly follow the church’s rules in his personal life. But the Communists had no faith. Kerouac yelled at the TV when they showed Khrushchev. His mother was making his pancakes and washing his socks. He was typing away at his typewriter too, when he wasn’t talking to fans who had climbed over the back fence, or he wasn’t at the local bar drunk again. Sometimes I wonder if my grandmother and Kerouac’s mother went to church at the same time in the same town. It probably happened, I think.

***

Neighbors later reported that mother and son fought a lot. What about, I don’t know. Nobody knew, because the Kerouacs’ loud arguments were in French. The youth of the town learned rather quickly that their new neighbor was the famous Jack Kerouac. It was hard for him to find a spare moment to write. They turned up at the front door, or chatted with him through the basement window. Kerouac even wrote about this in his 1962 book Big Sur. This was the first Kerouac book that I ever read. My girlfriend gave it to me when I was 16. I don’t know how much she even knew about Kerouac. Maybe she just bought it because of the title? But it was the right book for me. I especially liked the beginning. The story starts with Kerouac in San Francisco, waking up with a hangover to the sound of church bells. I went that summer to San Francisco and Big Sur and read that book along the way. There is one scene where Jack Kerouac is in bed with a woman and the woman’s child comes into the bedroom and watches. That was probably the first time I had ever read something like that in a book.

Through his life I learned that the world was much bigger and that adventures were waiting everywhere. That life was more of an interesting experience than anything else. Life was an experience, and a person could write about it as it happened, just like a photographer takes photos. His style was fluid, unique, and addictive. I think that once you get used to Jack Kerouac, it becomes harder to read more conventional literature. Books like Fifty Shades of Grey or The Da Vinci Code seem dull. Once you go on the road with Kerouac, there is no way back. And I am still on that road with Kerouac. In this way, I arrived at his old house, to take some photos of it and look it over. What did I expect anyway? That he would come outside, with garbage bags in his hands? That I would hear his mother yelling in the background? Ti Jean, my boy, your pancakes are ready! It was a hot, humid, and sunny day. Gilbert Street was quiet and empty. Some birds were singing away and there was a light breeze. The house is really just like any other. But when a writer like Kerouac has sat there with his typewriter, the importance of the house changes. People then come by and take pictures of it. They want to come face to face with the soul of that writer, at least just a little bit.

***

IT’S INTERESTING THAT Jack Kerouac wasn’t the only new inhabitant of Northport in 1958. Because my mother and her family showed up in town the same year. In some ways, my grandfather Frank and Kerouac were similar. Kerouac was born in 1922, and my grandfather Frank a year later. Kerouac’s home language was French. His parents were from Quebec and they moved to the US at the start of the 20th century to find work in New England, like many Quebecois did. Jack Kerouac’s real name was Jean-Louis Lebris de Kérouac. He attended Catholic school and his teachers were French-speaking nuns. Later, he praised the education he had received, and found that thanks to their rigid means of instruction, he had learned to write so well. I reminded my grandmother of this fact once when we spoke about Kerouac. To her, that crazy neighbor Kerouac wasn’t exactly an upstanding citizen, but the fact that he was a Catholic softened her position. Maybe he wasn’t so bad, she perhaps thought. If he was a Catholic, he was one of us. He just didn’t live his life the right way. Jack merely diverged from the road of Catholicism.

When he went to school, young Kerouac still didn’t speak English and had to learn as he went. He would study the dictionary to expand his vocabulary. It was the same for my grandfather. His parents were from Italy, and their home language was the Barese dialect. My grandfather also didn’t speak English until he started to go to school. A neighbor girl taught him how to speak it. My grandfather was ashamed of being different. He had a long Italian name. He had dark hair. For Americans, he was an outsider. Kerouac’s relationship with America was similar. He was an American in some regards, but he had a different perspective. He was both a local and a foreigner. But my grandfather lived a proper Catholic life. He was married by the age of 22. He had a job and five children. They lived on the edge of the City of New York, until one morning he took a ride out east to see what he could see. That’s how, one story goes, he discovered Northport, that same port town that Kerouac discovered around the same time. Both of them moved to Northport, and both took their mothers with them. Frank’s mother’s name was Maria. She made her son pizza, just like Kerouac’s mother Gabrielle made her son pancakes around the corner. In my mother’s home, they spoke both Italian and English. My mother is almost 77 now, and she still speaks English a bit differently. A professor of Italian once told her that she speaks like a child that has learned English from immigrants. The vocabulary and pronunciation are correct, but her sentence structure is a little off. The grammar is backwards, because she is using Italian grammar with English words. Sometimes I think that Kerouac’s bilingualism influenced his writing style. My mother never did meet with Kerouac, but her younger brother once recalled that on some nights he might have seen Kerouac, Neal Cassady, and Allen Ginsberg playing baseball. This was at the beginning of the 1960s. These were dangerous characters. Before there were punks, and before there were hippies, there were Beatniks. Ginsberg was a gay poet, and Cassady was simply a wild and crazy guy. Kerouac himself was not quite right. Some say that he hit his head too many times when he played football in school. Maybe that’s why he wrote so well? There are different theories.

I can only imagine how my uncle, then aged about nine, accidentally came across Kerouac, Cassady, and Ginsberg. Actually, they looked quite average. They just lived different lives. It was a warm summer’s night and he rode his bike by the baseball field and saw them playing. Just some Americans out playing baseball. Now that moment seems like a historical event.

***

Kerouac’s father died young, and when he was ill, a young Jack Kerouac promised his ailing father that he would care for his mother Gabrielle forever. This was a promise he made before God. So Jack was obliged to live with his mother. Or he was unable to leave her home really. Of course, he was married three times in his life, and he had one daughter (though he argued for a time that the child was not his, which was disproven by a blood test). A proper Catholic would have been married just once and stayed married. But Kerouac was unable to live that life. He had all kinds of worldly adventures, but the road always led Kerouac back home to his mother. His mother’s place was his main address. They lived in Northport until 1964.

They only lived on Gilbert Street for a year and a half before moving to Earl Avenue, into a small house on the edge of town with a Dutch roof. There they stayed for two years. Their last address was on Judy Ann Court, in a one-storey house. They spent three more years there. My mother’s family lived a few streets closer to the center of town. The story that my uncle claimed to have seen Kerouac playing baseball with the other Beats is probably true. Carolyn Cassady wrote in her memoir Off the Road how her husband Neil, Jack Kerouac and Ginsberg would go and play baseball together. For some time, Jack and Carolyn were even lovers. Neal was particularly supportive of their relationship, as he had cheated on his wife Carolyn many times. So if his wife had a lover, things would be more equal, he thought. Classic.

It’s interesting to read from time to time that Kerouac was gay, like Ginsberg. Even Gary Snyder, who is 94 at the moment, and who inspired Kerouac’s character Japhy Ruder in his novel The Dharma Bums said in a recent interview that Jack hated women and was probably gay. But then we have Carolyn Cassady who writes about her passionate relationship with her husband’s pal. I’ve also read Joyce Johnson’s book, The Voice is All: The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac. Johnson described a very charming character with blue eyes who whispered to her in French. Johnson, who is also a successful writer, was Kerouac’s girlfriend for several years. She once wrote that in the world of the Beat Generation, women were girlfriends or muses, but she wanted to be more. She also wanted to be a writer. This fact has really stuck with me, although I have been quite similar to my Beat predecessors in terms of my own perspective.

But Jack Kerouac always had some woman. Always. One of these was the Afroamerican Alene Lee, who inspired his character Mardou in The Subterraneans. This book has been translated into Estonian. Its Estonian title is Pilvealused and the translator was Triinu Pakk-Allmann. The second novel to appear in Estonian is On the Road, or Teel, translated by Peeter Sauter. The most colorful female character in On the Road is a Mexican woman named Terry with whom he lived a while in California. One of my favorite quotes in the book belongs to Terry when she says to Sal Paradise, the main character, “I love love.” Johnson wrote that this relationship was one of his most stable, and that Jack might have stayed together with Terry, who gave him the freedom to roam. But no. Kerouac promised his father that he would take care of his mother. True to his word, he did so. His responsibilities to his family were his priority.

The writer Gore Vidal once wrote that he had a relationship with Kerouac though. And Joyce Johnson acknowledged there had been some intrigues with Ginsberg. Sexuality among the Beats is an interesting topic, especially because at that time in the “hetero world” things were just different. Men would go to visit prostitutes together. Jack writes about spending time with Mexico City prostitutes. It was just a regular thing. “Guys, let’s go get some prostitutes!” Even Ginsberg went with them. What did he do there? Read some Mexican girl one of his poems?

One of Kerouac’s loves was certainly Tristessa, a young Mexican junkie. Her real name was Esperanza. It’s hard to think that a man who wrote so much about women was gay. But maybe it would be more honest to accept that things have changed since those days. In the 1950s, there was limited awareness of the LGBTQ+ community. There weren’t parades with rainbow flags. Neal Cassady could sleep with Ginsberg and his wife Carolyn and not lose any sleep wondering about which letter best described his sexual orientation. Was he bisexual? Pansexual? Omnisexual? Was he a G, a B, or maybe even a Q? Neal was just Neal, and Jack was Jack. It was just a different time. In Joyce Johnson’s book there is an interesting fact that Jack didn’t think of himself as being gay, but that he actually wanted to be gay. Most of the best writers of the day were gay. Gore Vidal. Truman Capote. James Baldwin. He was almost ashamed that he wasn’t, because everyone knew that gay writers wrote so well. This fact really astonished me. It was like an inverted reality. Maybe it’s inspired me to write more honestly about women. Men’s interest in women is deep, intriguing, at times terrifying, but inspiring. There is more to unearth from that treasure trove.

***

MY GRANDPARENTS WERE devout Catholics, but Kerouac had a long relationship with Buddhism. Carolyn Cassady recalls in her memoir how Jack found Buddhism and started to believe that the world was an illusion and that reality was just emptiness. He tried to live as the Buddha. He even wrote Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha and The Dharma Bums during this period, as well as Desolation Angels. I have read The Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels, but Wake Up hasn’t found a place on my bookshelf just yet. I understand that he had personal problems, especially with alcohol, but also within his family system, which kept him in a sort of personal prison in life. Other people got to enjoy their freedom, but he had responsibilities. He could travel and write, but his mother was still waiting for her boy at home.

Carolyn acknowledged in his memoir that the new, Buddhist Kerouac wasn’t exactly a barrel of laughs. He became very stern and serious. He went up to a mountaintop in the summer to contemplate emptiness. Kerouac no longer wrote to his friends about his thoughts, but about the dharma. He was looking to be liberated from himself. As a Catholic, his life was full of disappointment and guilt. In both the family and the church, there was a lot of confusion, stress. This I understand well. I started school in Northport, and my first school was a Catholic school. Kerouac was, by that time, dead. He died in the summer of 1969. He was 47. When I was younger, 47 sounded kind of old. Now, at the age of 44, it sounds like a teenager to me. I was born a decade after Kerouac died. I started school six years later, as I said, there in Northport. These facts are not so deeply connected to me or my life story. They are just a coincidence. Because I didn’t know anything about Jack Kerouac’s Northport period when I was a little boy.

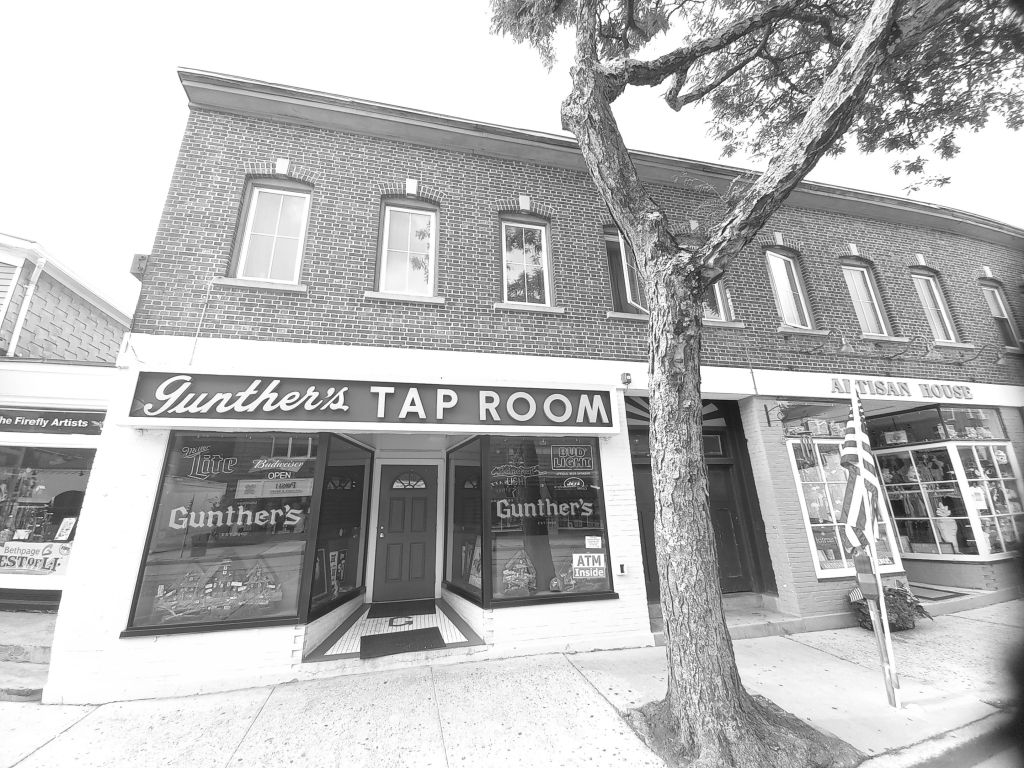

Still, his world was familiar to me. My grandfather died in Northport two summers before Jack. A heart attack. My grandmother lived long. Her house was full of crosses and angels. Lots of shining angels. My father’s uncles had a bar in Northport, but Kerouac’s favorite bar was another one called Gunther’s Tap Room. These days, Northport is a wealthier place. At that time, in the 1950s and 1960s, it was a rougher, working class down. There was a sand and gravel company nearby, and on their lunch breaks the workers would come to town, eat and drink. There were a lot of drunken bar fights. Pete Gunther, the bartender, who was the original owner’s son, was a teenager when he started working. He’s now long dead, but when I was 25 and working for a local newspaper, I met up with him and interviewed him about Jack Kerouac. There was even a sign on the wall that said, “Kerouac Drank Here.” Apparently, his alcoholism intensified during this period.

Pete Gunther, a bald older man with a round face, in general quite friendly. He told me straight that Jack Kerouac was a drunk. He was drunk every day of his life. This was like the scene in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden when the good son who believes his mother is dead finds out that she is very much alive and running a whorehouse in town. “Justin, your greatest hero was just some crazy drunk.” That’s what Pete Gunther related to me in our interview, more or less.

Jack once gave Gunther an autographed copy of one of his books in exchange for a beer, but Pete Gunther said he couldn’t make any sense of it. It was all crap, he said. He didn’t understand it. So he threw Kerouac’s book in the garbage. In some ways, I feel it was symbolic of how America treated him. Now that the original scroll of On the Road is displayed in museums, we can think that once upon a time a great writer lived in that small house over there. Or put up a sign that says, “Kerouac Drank Here.” Or try to collect memories of him from other people, people who once met him, or saw, perchance, him playing baseball with his friends. That summer when he died though people were more interested in hippies, the Vietnam War, and the Prague Spring. His best friend Neal had died a year prior in Mexico beside the railroad tracks. He was known to use drugs, but it was the rain and his lack of clothing that did him in.

When Neal died, Kerouac told his friends that he wanted to join his best friend in heaven. The writer and poet Gregory Corso, who you can see in Jack’s short film Pull My Daisy together with Ginsberg and the other Beats, recalled similarly. “Jack wanted to die,” he said. And so he did. He got into a bar fight and started bleeding inside. In the end, it was life-long alcoholism that took the life of Jack Kerouac. But he did want to be with the angels. Mr. Corso said so.

That morning, as I was looking over his first Northport home, I sat in my car for a while. I wanted to tell my old friend Jack not to drink so much. Leave your mother Gabrielle behind and go live with that Mexican girl. The one who said she loved love. Or some other girl. Or maybe even multiple girls. Life is for living, Jack. It’s too soon for wrestling with those angels.

When I was 16 and my girlfriend gave me my first Kerouac book, Big Sur, I started to write. I had read how Jack always had a notebook on him, and that he would write everything down. I can now see traces of that book in everything I write. So Kerouac continues to live on, quietly.

Here and there.

An Estonian version of this article, written by the author, appears here in the magazine Edasi.

Kerouac’s three Northport houses.